Feudalism

Feudalism or manorial regime: mode of production based on a "feudal bond". The ruling class takes charge on a family basis of the exploitation of a territory and its inhabitants by virtue of a bond or vow of vassalage which also orders and hierarchizes the relations between the different layers and groups of the exploiting class.

General features

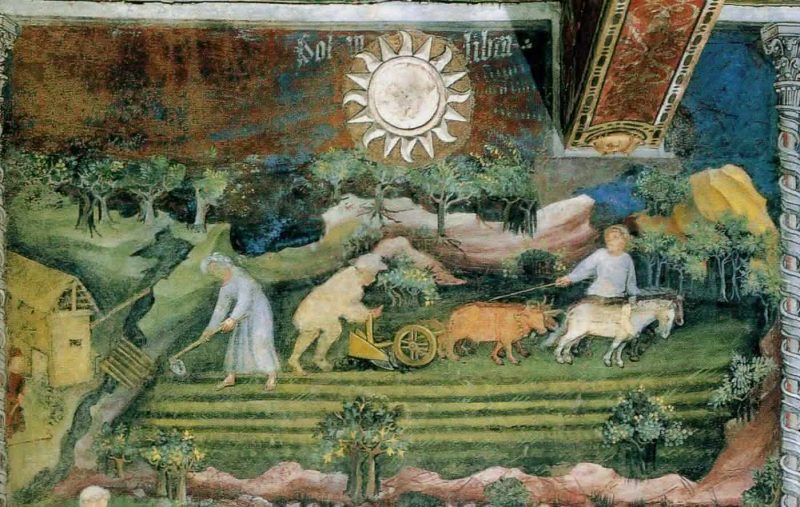

During feudalism neither the labor power of peasants nor the land they worked on could be sold on the market. They both were not commodities.

Widespread throughout Asia, large parts of Africa and Europe at different historical moments and projected towards America by the conquest by the Iberian monarchies, feudalism is not a universally homogeneous mode of production. In fact the diversity and particularity of customs and "privileges" in small territorial portions is a fundamental element of its stability, by blocking the way or at least hindering commodification and trade.

However, all these feudal systems share a number of common features:

- Exploitation takes place by fundamentally extra-economic means and takes the form of exactions of production and/or working hours.

- The exploiting class (the nobility) has no legal ownership over the exploited class even though the peasants are legally bound to the territory to which they "belong."

- Practically the entirety of both the labor power and the principal means of production, land, are not commodities.

- Class differences are extremely marked and, in urban areas, minutely regulated and demarcated by sumptuary laws and codes.

Social classes under feudalism

During feudalism neither the labor power of peasants nor the land they worked on could be sold on the market. They both were not commodities.

The fundamental classes of feudal society were the nobility (exploiting class) and the peasantry (exploited class).

In a system with very low land productivity and a very marked difference in the ability to satisfy the most basic needs, the size of the ruling class tended to increase much more rapidly than those it exploited. Thus, in virtually every expression of the feudal mode of production, the ruling class developed a clergy and monastic systems - from christendom through islam to buddhism - which served as an ideological factory, colonizing agent and repository for the ruling class.

The peasantry will prove, despite the continuous revolts that will proliferate during the feudal decadence, incapable of asserting a historical alternative, a role reserved for the bourgeoisie. Its program in all cases and until the establishment of capitalism, was reduced to the defense of communal lands under various banners and nearly always laced with apocalyptic overtones, from the German peasants in the sixteenth century to the Taiping and Donghak rebellions in the nineteenth century.

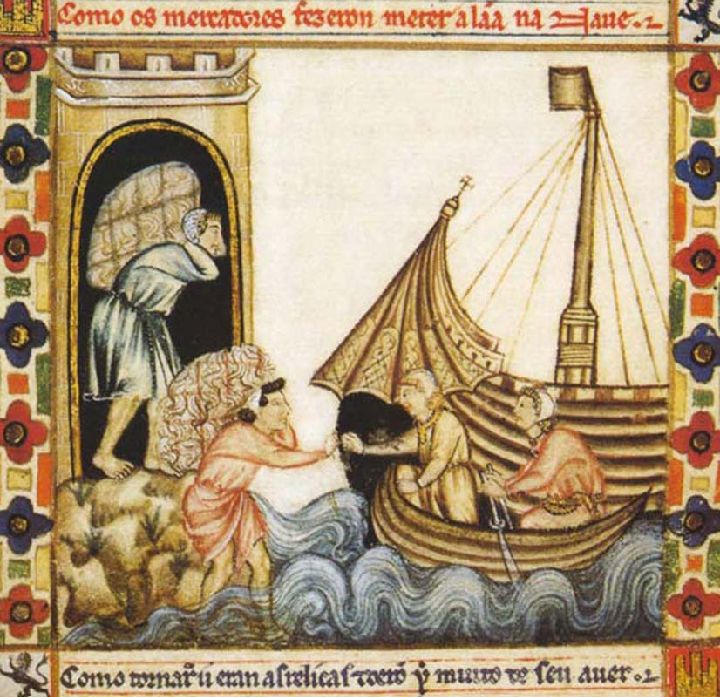

An extremely regulated and repressed class in Asia, it was only in Europe and from the 11th century onwards that the bourgeoisie was able to develop sufficiently in order to assert itself as a revolutionary class. And yet, between its first attempts at political revolution (Castile in 1520, Flanders in 1568, England 1642) and its first lasting successes (US independence 1776, French Revolution 1789) it took more than two and a half centuries.

Along with these three main classes there coexisted, in different contexts, both salaried workers and slaves. One or the other will be able to become numerically and economically relevant at a local level without becoming a historical alternative or putting feudalism as such in question.

The feudal state

Louis XIV. Ceremony of the "awakening" of the King. The development and concentration of powers in the King and his apparatus worked to contain the conflict between bourgeoisie and nobility within the framework of the old statutory legal relations.

Until the decline of the feudal system, the nobility locally and directly exercised state and governmental functions. The nobles were "lords of lives and estates". Hence people often emphasize the decentralized character of feudalism. Although, once again, this decentralization was not homogeneous even within Europe, even less so in the Arabic-speaking world, and both the monarchy and the clergy would at different times attempt to reorganize and centralize the ruling class.

In reality, it was not until the decline of feudalism that the main European monarchies (Castile, England, France) and the Ottoman sultanate laid the foundations of a true "state feudalism", later known as the "Ancien Régime".

This is when feudalism develops a relatively voluminous state, autonomous from the individual nobles. The "private wars" between noble families will be extinguished. The first criminal investigation systems (the Inquisition) and the first centralized judicial and police bodies (commanders and royal bailiffs) appear. And a whole bureaucracy flourishes around the court and gradually gains functions in the territory.

During the course of feudal decadence and especially from the 16th century onwards in Europe, the state will become a battleground and merging ground between the nobility and the rising bourgeoisie. The equilibrium will come in the terminal phases of the Ancien Régime, preparing and foreshadowing the takeover of the state apparatus by the bourgeoisie.

http://dictionary.marxismo.school/FeudalismAs an exception, there are periods in which the classes in struggle are so balanced that the power of the State, as an apparent mediator, acquires a certain momentary independence with respect to one or the other. In this case is the absolutist monarchy of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, which kept the balance level between the nobility and the bourgeoisie.

The Origin of Family, Private Property and the State, Engels, 1884